Why Netflix, Amazon, YouTube and PlayStation reducing their traffic won’t save the Internet

Media Published on •5 mins Last updatedCan the tech giants actually improve Internet performance – or is it just good PR?

Netflix recently began streaming HD and 4k content at lower bit rates to reduce the load on Internet service providers (ISPs). With such an unprecedented shift to self-isolation and home working, the streaming service hopes to reduce its network traffic by 25%.

The move came after calls from the EU to "preserve the smooth functioning of the Internet” while most of us work and live almost exclusively at home.

YouTube, Amazon, Disney and Apple’s rival video services all quickly took similar measures, both in Europe and the US, while Sony Interactive Entertainment and Valve also amended the PlayStation Network and Steam gaming services respectively.

But are these measures meaningful in freeing up bandwidth to ensure that critical systems remain flowing? Or little more than a gesture to show tech’s titans playing nicely with global leaders to 'do the right thing’?

Designed to be dynamic and robust

Under normal circumstances our experience of the Internet at home, while mobile and at work is pretty consistent.

Usually, hundreds of thousands of businesses across the globe connect to various sites, partners and customers 24/7, sending huge amounts of data at low latency every second of every day.

Zero downtime is often the number one priority for businesses, because downtime impacts service, which impacts customers – which impacts revenue. So businesses are more than willing to invest large sums in robust and resilient enterprise-level telecommunications solutions.

Everything required to keep corporate offices running – including apps, VoiP, SaaS solutions, ByoD – rely on expensive direct connections to ISPs 100G networks. Extra resilience comes from connections to multiple local exchanges (a back-up if one encounters problems), or a mobile backup system if the primary network fails. In the US, if you need the best coverage, high-speed satellite Internet beats traditional telecommunications networks.

Much of the bandwidth supported by this infrastructure is used by ongoing business operations (data storage, systems, backups, websites) but some of it enables day-to-day communication and processes for employees too.

So what happens if you shift a call centre from a local on-site phone network, to VoiP over agents’ home broadband connection? Or ask the workforce of a large office to forget their cumbersome desktop PCs in favor of always-connected, cloud-based remote desktop clients on their home laptops? You also stop them talking face-to-face in favour of Microsoft Teams, Google Hangouts or Zoom. Beyond the 9 to 5, don’t forget to ask everyone to do more online shopping, browse online more often, use more web-based communications platforms, play more videogames and stream more music and video. Multiply tens, if not hundreds of thousands of times.

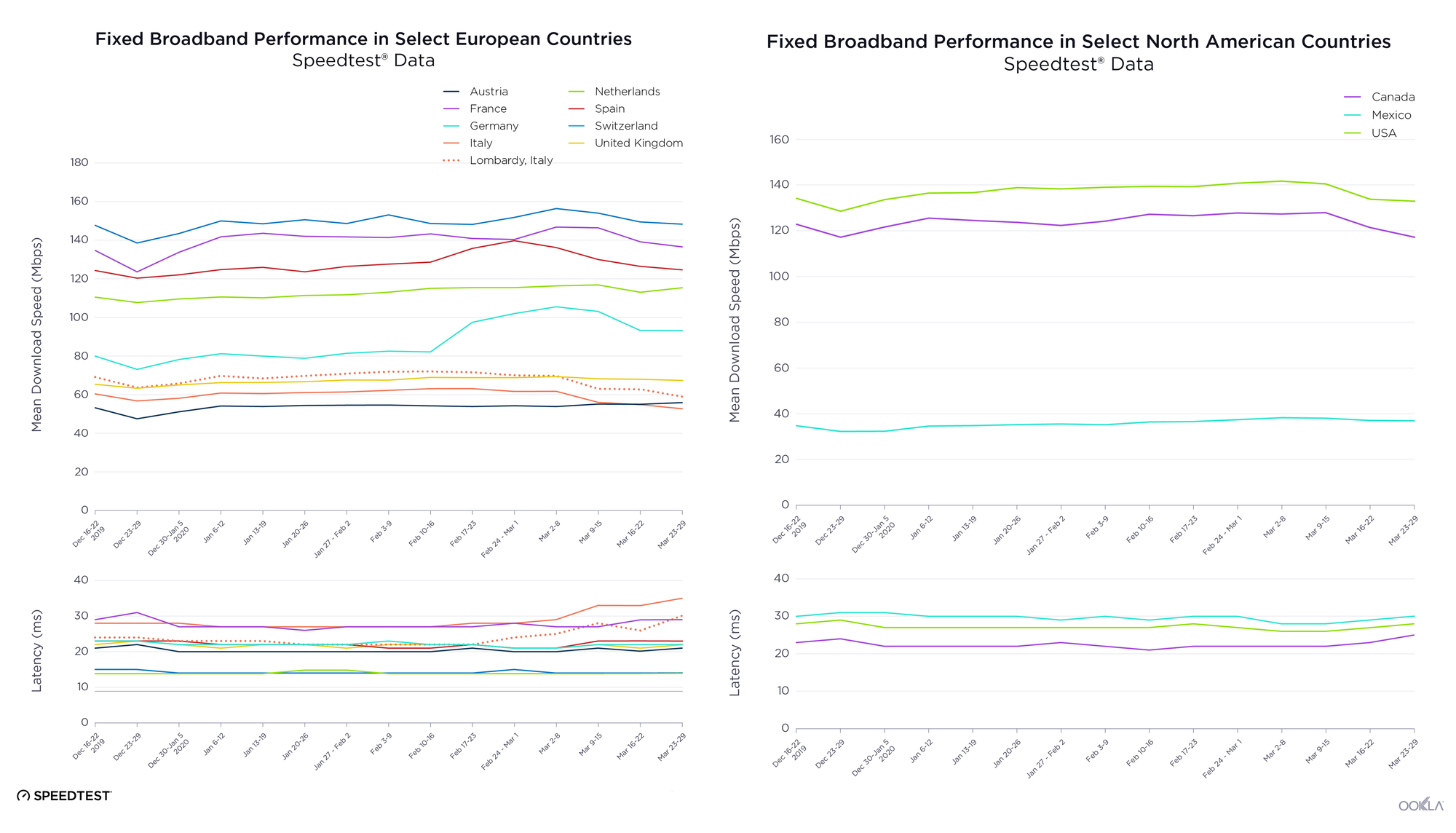

The reality seems to be that this massive traffic shift to consumer ISP infrastructure hasn’t affected the efficiency of the Internet much at all (so far). According to net speed analysts Ookla, there have been some slight decreases in traffic speed in some of the US and Europe’s worst-affected regions, as well as China, which has since seen a slight improvement as the situation there improves.

It’s not you, it’s me

Ookla measures the speed of user's connections, rather than the speed of network infrastructure itself. So, the speed decrease may be less about overloaded Internet infrastructure and more related to congested home Wi-Fi routers, now under more demand from families trying to stream video, teleconference, game and download concurrently in different rooms. In the UK, regulator Ofcom has put together some top tips for staying connected at home.

ISPs build their networks differently, for different scenarios (ie urban or rural) – but all will have an idea what their peak traffic looks like – now, and in the future. Discussing the different constraints global ISPs face, Netflix’s own press release confirms “some ISPs build their networks with a substantial amount of excess capacity (“headroom”) others do not.”

Not all ISPs are equal

Spanish telecommunications firm Telefónica reportedly reached all the extra capacity it planned for 2020 in just two days. Although the major UK network provider BT Openreach is now experiencing 83% more traffic between 9am and 5pm, it’s daytime traffic was reportedly peaking at 7.5Tb/s rather than the daytime norm of 5Tb/s. The all-time peak of 17.5Tb/s was driven by the Merseyside derby soccer match and video game updates.

“We have more than enough capacity in our UK broadband network to handle mass-scale home-working” reads BT’s response. “Our network is built to accommodate evening peak network capacity, which is driven by data-heavy things like video streaming and game downloads.”

“By comparison, data requirements for work-related applications like video calls and daytime email traffic represent a fraction of this. Even if the same heavy data traffic that we see each evening were to run throughout the daytime, there is still enough capacity for work applications to run simultaneously.”

The need for GSLB (or not)

We added global server load balancing (GSLB) to our products for reliability and efficiency, ensuring local users go to local resources - minimizing latency and the chance of encountering network problems.

But Netflix and the other tech giants have no real need for GSLB, instead working with ISPs to operate their own Content Delivery Networks (CDN) locally in each territory. Netflix’s CDN, Open Connect, is essentially a series of giant hard drives containing all of its content, which it can embed locally with ISPs for high availability and low latency for the end user – ultimately pushing data through a smaller section of the network.

“Your ISP’s connection to your home, your modem or router, the number of connected devices in your household, and other activity on your Internet connection can all impact the quality of the video you receive,” reads Netflix support.

We’ve all experienced a choppy video from time to time, whether on YouTube or Facetime. But traffic is traffic – if there’s too much at the same time, it tends to degrade or slowdown, not stop altogether.

Web security firm Cloudflare has tracked the recent growth in traffic from residential broadband networks, and the decline of traffic from businesses and universities, but notes: “The core of the Internet is robust. Traffic is shifting from corporate and university networks to residential broadband, but the Internet was designed for change.”

We’re in the middle of the biggest shift to a home-working culture there’s ever been. Maybe after all of this is over, some companies and employees won’t look back. But the good news is that much of our network infrastructure was already designed for additional traffic – and the reliability of your connection probably has more to do with tech in your home and the demands you put on it rather than what Netflix, YouTube and the other Internet titans do at their – which, hopefully means zero downtime for the critical services we’ll all need to get through this uncertain time.

For more on how we ensure zero downtime for our customers, visit loadbalancer.org.